Performance view of Ricky Yeung, “Out of Context,” 1987, 15 Kennedy Road, Hong Kong

Courtesy Asia Art Archive

A small-scale exhibition, “Excessive Enthusiasm: Ha Bik Chuen and the Archive as Practice” showcases the initial results of Asia Art Archive’s research into the late artist’s life, work, and personal archive. The objects displayed, which represent but the tip of the iceberg from Ha’s vast database, are selected in an attempt to demonstrate the different possibilities of reading a document.

Hong Kong artist Ha Bik Chuen (1925-2009) was initially known for his sculpture and printmaking. Later on in life he turned his attention to photography and ink painting. The image of Grandpa Ha, as he was affectionately known, walking around with his cameras was constant over 30 years of exhibitions spanning every size, format, and location; his perseverance as a documentarian is truly marvelous. After his passing, the art database—which he called a workshop for thinking—was fully preserved: the collection fills a room of 600 square feet covered wall-to-wall by bookshelves lined with boxes of negatives, books, and photo albums. The shelves are arranged in a system known only to Ha himself; deciphering this system and inventorying the collection is a difficult task. Following an initial survey, the archive has been divided into four main categories: photographs of exhibits and art events; photographs of art; records of Ha’s own artwork; and books and catalogues. The collection covers a vast range and depth of materials providing the foundation of a pluralist art history.

Between the 1960s and the turn of the millennium, Ha photographed over 1,500 exhibitions and art events, mostly in Hong Kong, and their documentation comprises a rare collection of raw material. Photography, for Ha, was a form of creativity as well as documentation; it was a means for him to hone his work and capture inspiration. He recorded shapes and visual elements that he found interesting around the city, and copied copious amounts of photographs and prints from books and periodicals. This practice of visual collection resulted in a number of individual artist albums for European artists such as Joan Miró, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso, as well as Hong Kong artists including Cheung Yee, Van Lau, and Ho Siu Kee.

Ha systematically digitized his photographs and stored the negatives, contact sheets, and photographs in albums. Each roll of film is stored with the contact sheet, and over the years some 3,500 were ac cumulated. They are each methodically marked with both technical details and notes on Ha’s state of mind at the time. For instance, a contact sheet marked “Luis Chan’s Studio / 7-4-83 / 58” includes details of a durian shell, wooden Arabic carvings from the Quran, primitive wooden sculpture, Luis Chan himself, Chan’s studio, and pieces by other artists, including Ju Ming—essentially Ha’s visual diary. A contact sheet marked “ART / 108” includes shots of art publications; the white space surrounding the original prints is carefully arranged to form a frame for the photograph, demonstrating the painstaking care he took in his endeavors.

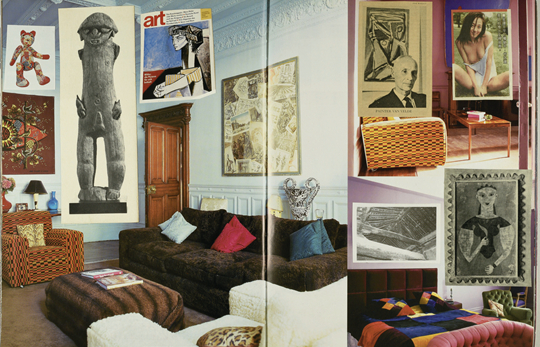

Ha’s fascination with found objects and collage is apparent in his work, and further reflected in his tireless visual collections. He collected images from newspapers, magazines, and other popular culture formats, archiving them in photo paper boxes assembled into albums. In one, he pastes photographs of girls in bikinis, artists, indigenous African art, international news articles, and fonts that interested him into the pages of a large-format interior design book. His collages engage the original book in a conversation, bringing together reference and creativity. Michelle Wong, the researcher responsible for disentangling Ha’s archive, believes he was creating an exhibition on the pages themselves. More than 20 of the 2,000 volumes in the library belong to this category of collage exhibitions.

Artist Kurt Chan, who teaches in the Department of Fine Arts at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, writes about Ha’s documentation methodology in his article “A Self-Made Artist”:

Deprived of formal schooling in hist tender years, Ha Bik-chuen’s self-directed art education relies chiefly on the visual: to feel with the heart what he saw with his eyes, and to interpret with his own mind. This ‘intuitive’ approach to art interpretation is not in itself problematic, as it is especially apt for art that speaks through its own visual attributes; but unavoidably it would cause a certain kind of ‘misreading’ when art entered the conceptual age. … Such approach to art education based on retinal reception and intuition often fails to grasp the essence of contemporary art, but it somehow brings a new kind of ‘re-creation.’

This methodology of recreation through misreading, an intellectual move that translates a portion of the subconscious into an image, is a door between dimensions that allowed Grandpa Ha to traverse freely between his own life and the various visual worlds of his own creation.